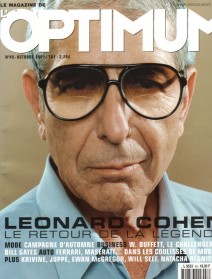

|

| Photo by Michel Figuet |

Optimum (Opt): You went away for a long time. What happened during all those years:?

L. Cohen (LC): I finished my last record in 1993. After that I went to live on Mount Baldy, in a Buddhist monastery located about an hour and a half from Los Angeles. I remained there for five years. I then return to the city, and although I remain very close to the monastery, little by little I began to work on this record album with close friends in my personal studio.

Opt: It is surprising to see you return with a new album, when many believed you had definitely ended your musical career...

LC: The fact is that I lived in this monastery and that I devoted myself entirely to that community way of life. I meditated, I was a cook for my spiritual teacher and I continued to write. Some of the songs on this new disc were created during that time. But at a certain moment, it seemed that I had reached the end of that period. I therefore asked my teacher for permission to leave the monastery. He granted it with his blessing. And thus, I returned to civilization. Then I left for India for several months. I went there alone with the aim of meeting a writer, Balsekar, whose work has fascinated me for years. Then I finally returned to Los Angeles to resume working on the record with Sarah and Sharon, two friends and very close collaborators.

Opt: Why did you release a disc instead of a book, which would have be simpler?

LC: I have a book which has been ready for several years. It is a collection of poems, small stories and blackened pages. There are more than 250 pages and to finally sort through them seemed more difficult than working on a new album. With regard to the book, I do not feel any particular urgency.

Opt: This lack of urgency seems essential for you. As if your own rhythm prevails over the world around you...

LC: Absolutely. I work slowly and like to be sure of my efforts. There are people who write marvellous songs or poems in the back of a taxi cab. I would have loved to have this talent, but that is not the case.

Opt: Is this allowance of time, this nonchalance with regard to creation increasingly rare for artists today?

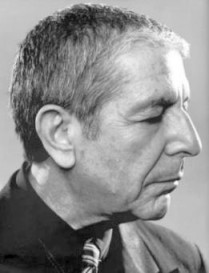

|

| Photo by Michel Figuet |

LC: The economic need is such that the majority of artists are engulfed in the breach as soon as their name is extracted from anonymity. They want to create as much as possible so they can be famous. Personally, I never had any significant material needs during my life. Of course, I had children, I took care of their education so they had as many opportunities as possible. Besides, during my career, I could not see what would justify this state of urgency. And even if this state is more and more recurrent with people, including artists, that no longer concerns me.

Opt: After your retirement, what were the principal changes in the musical creation process that you followed after your "resurrection"?

LC: I have always utilized the same process, a certain level of relaxation. For this album, for example, we worked at my place, at one end of an old garage. Everyone was in the same rhythm so there was no dissension. And that agreement produced this disc. When I was a writer, at the beginning, the process was different because I worked alone, but here, it was team work.

Opt: Is this balance between solitary work and the collective creation required?

LC: It refelcts a bit of what I need. But you know, the life in the monastery is far from the stereotypes of Trappists that we have. It is not a life of solitude, on the contrary. This is an atmosphere where one interactions with other people, where one moves daily with others, and thereby is improved. That forms part of the philosophy of the monastery. On the other hand, my life in Los Angeles, in the city, was much more solitary. Even if my children didn't live very near me, it is there I feel most alone, and not on the mountain.

Opt: Now that you have returned to civilization, what is the principal lesson you learned during your years spent in Zen meditation?

LC: I believe that the goal of this experiment was to forget myself, to forget oneself. One sits for hours meditating until one reaches the point of being so tired that one doesn't have any other choice but to progressively disintegrate.

Opt: Does one finish by forgetting his ego then?

LC: For the ego, it is still different. The ego is very hard to master and it is very rare that it agrees to commit suicide.

Opt: Did this experiment allow you to find a certain kind of freedom, to free you from the contingencies of civilization?

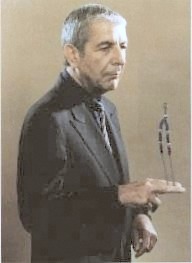

|

| Photo by Michel Figuet |

LC: When I went there, I went neither for spiritual questions, nor to find another religion. I already had one that suits me. It was more a question of my managing a structure as a human being. And also to follow this spiritual mentor who had strongly impressed me during our first encounter, long ago, and whose company I knew would only be beneficial for me. He knew so much more than I that I knew I had to follow him in that moment. And with this intention, I did not have a choice but to become a monk during those few years. At the end of this experiment, I could return because I did not have any special spiritual talent, that I was not a healthy man, as compared to him. When I finally realized this, it was time for me stop. Therefore the principal revelation I had thanks to these years of meditation is that I did not have an particular religious aptitude. This allowed me to return to the numerous contentious zones in which I live. And consequently, today I am more at peace with myself. To me, this has been a very great help.

Opt: I am curious, on your new disc, your lyrics seem lacking any spiritual approach, which was not always the case.

LC: Indeed, and one can certainly find the reason in what I just explained.

Opt: They are also extremely simple. Was this deliberate?

LC: I do not know. It would be very pretentious to affirm it, in as much as one does not really control these kinds of things. They are imposed on you rather than you directing them.

Opt: "I belonged at last to Babylon" is a line that one hears in your new song, "By The Rivers Dark." Why this strange desire not to be excluded from Babylon?

LC: This song reports the peregrinations of a character from Babylon. He stays there, then flees it, then returns, etc. He belongs to the city of turpitudes while knowing that there exists somewhere this Jerusalem that some share, but without knowing too much about it, he returns. It is a little like our thoughts. Just as we are a receptacle for love, our brain is filled with thoughts. One does not know what will arise in us in the next second. But our nature encourages us to believe that we must control these flows. However, we do not control them anymore than the place we were born. One spends far too much time thinking that one can disparage or deny our origins or our condition. And this is the story that is reflected in the character, except in the end he really understands where he comes from; and even if there is an Eden somewhere, he comes from Babylon and must accept it, and this will surely enable him to better appreciate the idea that he is from somewhere else possibly better.

Opt: In this song you also describe two rather paradoxical ways of life. One pious, the other more hedonist. Are these two universes such that you cannot explore one without the other?

LC: Of course! Babylon is what I call "Boogie Street," it is where we are without any real possibility of escaping from it. And many of the songs on the album speak about this, of the reconciliation between these two ways of life, because finally, it may very well be that this Holy city of Jerusalem sits right in the middle of the kingdom of sins, and we are prisoners of these two kingdoms and can never be in one forever.

Opt: What is your opinion of the recent evolution of our society?

LC: I do not have any real point of view on that. I really do not understand what occurs, particularly in the west. Everything is so complex. The balance of these things seems so precarious. One always has the impression that the beginning of chaos has arrived, and then one wonders whether it has not always been like that, if this isn't the energy of civilization. As if we had a perpetual need to have this sword of Damoclès over our heads. With regard to Europe, I cannot speak much because I have not lived there for a long time, but here in America, this energy that draws us near to chaos is fascinating. It generates such a high level of activity that it almost becomes tiring to contemplate it.

Opt: However, don't you have the feeling, as a musician or a poet, that it is less and less complicated for people like you?

LC: First, I never regarded myself as a poet. This word is a verdict which equates with death. A writer, perhaps! With all that happens, I believe that society is increasingly hard for everyone, not just artists. This is all the more paradoxical because we are in an era when we've never been more rich.

Opt: What are your memories when you remember the time you lived in Greece, on Hydra?

LC: That was a unique and wonderful moment. Unfortunately, at the time, I did not realize it as intensely as I do today. It is funny that you should speak about it because I have gone back there for a short while. And all returned to me. I always had a house over there, which I had bought for 1500 dollars and which I adore. Even my son said to me the other day that his memories of his time there formed the best part of his childhood. It was almost too good or too beautiful to be true.

|

|

|

|

|