|

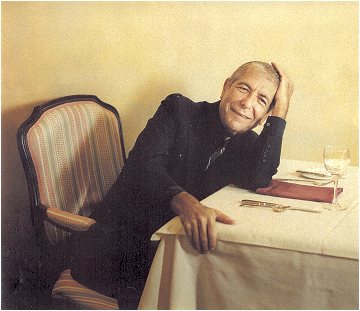

| Photograph by Gabriel Jones |

The city knew immediately that he was back. From the mansions on the hill, to the panelled downtown watering holes still mourning Richler, past the cranes latticing the skyline of old Montreal and fanning out across the Plateau, the news spread. Leonard Cohen is down from the mountain! Down from the Zen Center at Mount Baldy, California, where he, still a Jew, but also an ordained Zen Buddhist monk, has been solemnly cooking vegetable soup for his teacher, Roshi, for more than ten years. There were sightings: Cohen walking on Rue St-Denis, Cohen whistling in Parc Jeanne-Mance, Cohen ordering a shawarma on the Main. Except for the funeral of Pierre Trudeau, where he was an honorary pallbearer, Cohen had not returned to his Montreal home in six years. So the bars and cafés were abuzz, and, as the longest, strongest heat wave in recent memory ravished the city, everyone wondered what condition he was in. He is, after all, sixty-six years old and, following the recent deaths of Trudeau, Maurice Richard, and Mordecai, one of the city's last lions.

Cohen was in town to promote his first album of original material in nine years, Ten New Songs. My interview was scheduled to take place at his home, a greystone in the Plateau, just off Boulevard St-Laurent, skirting the mountain. The brooding poet at home, his home. It seemed too good to be true and it was: that morning, the PR rep from Sony left a frantic message on my answering machine. "Change of plan! You will be meeting at the Vogue Hotel," she blurted. "It's 100 degrees and he has no air conditioning." The Vogue is full of seafoam-green carpeting and cheery "Hi, My Name Is. . . ." name tags -- not the kind of place for the ambassador of melancholia. "We'll meet you in front of the hotel," she said.

An hour or two later the PR rep is there, holding a box of Godiva chocolates she bought "just to make Leonard happy," but he's already gone up to his suite. We follow and there, pigeon-toed on the seafoam, in a tailored black suit with a bright pocket square and smoking a Vantage, putting on sunglasses quickly like a hipster caught in the headlights, is Cohen.

"Oh, hello," says that voice. "I thought we would meet in the lobby but then I saw you two ladies mounting -- I'm sorry, taking -- the elevator." He smiles. "It's so hot outside. . . . Would you like to take a shower?"

I don't know what I was expecting him to be like. More moody, perhaps. Not like this, not animated, not so gracious, not eager to see me at ease. Not chipper, like a butler on his first day back on the job after a restorative vacation. And not offering me a shower. "Would you like a chocolate? I have a particular weakness for them." No, thank you. He claps his hands. "Please, then, have some coffee." We sit down at what looks like a boardroom table. "Here," he smiles, offering his Styrofoam cup of café au lait. "It's delicious. We can share my cup . . . together."

I sip. He sips. He says, "Yum!" I reconsider every question written in my notebook, because Leonard Cohen just said -- no, exclaimed -- "Yum." "Now, dear, what exactly would you like to ask me?"

His exuberance has left me at a loss: "Are you taking any drugs?"

"You mean, like, medication?"

"Yes, like, prescribed stuff."

"No, not now. I was taking things like Prozac for depression, but none of those antidepressants worked."

"Which have you tried?"

"Oh, let's see. I was involved in early medication, like Desipramine. And the MAOs [monoamine oxidase inhibitors], and the new generation -- Paxil, Zoloft, and Wellbutrin. I even tried experimental anti-seizure drugs, ones that had some small successes in treating depression. I was told they all give you a 'bottom,' a floor beneath which you are not expected to plunge."

"And?"

"I plunged. And all were disagreeable, in subtly different ways."

"How?"

"Well, on Prozac, I thought I had attained some kind of higher plateau because my interest in women had dissolved." He laughs. "Then I realized it was just a side effect. That stuff crushes your libido."

"Oh dear. You can't have that."

|

| Photograph by Gabriel Jones |

"No. So one day, a few years ago, I was in a car, on my way to the airport. I was really, really low, on many medications, and pulled over, I reached behind to my valise, took out the pills, and threw out all the drugs I had. I said, 'These things really don't even begin to confront my predicament.' I figured, If I am going to go down I would rather go down with my eyes wide open."

In 1979, Leonard Cohen was interviewed by Patrick Watson on the CBC television series Authors. Among Cohen cognoscenti, the interview is considered something of a must-see, perfectly encapsulating a certain period in Cohen's public life. In a green velour blazer, Watson, who went on to become the president of CBC, is seated in front of a modestly suited Cohen, who in those years, smoked using a long black cigarette holder. The studio lighting is brash as Watson lobs pretentious questions at Cohen, the kind previously known to get his back up. Not only does Cohen raise no eyebrows -- and you wish he would -- but he barely moves during the entire interview, accepting the snootiness as it is served. His eyes seem to be staring past Watson, at something just awful. His words are delivered in an excruciating monotone.

In those days, the damp sheet of depression which had always lain lightly upon Cohen had become a sopping blanket. His life was engulfed by it. His marriage had collapsed in bitterness, and while he had recently kicked hard drugs he was still unable to finish a long overdue manuscript. The hostile reception of his fourth album of original material, Death of a Ladies' Man, had sent his recording career into a nose-dive. It had been over a decade since the bar-mitzvah boy croakings on songs such as "Suzanne" and "Bird on a Wire" had made him an unconventional, international sensation, and he felt he had since "drowned." On the Authors segment, the interview ends with Cohen telling Watson that for him, it is even "too late for suicide."

"My depression, so bleak and anguished, was just crucial, and I couldn't shake it; it wouldn't go away," he says, looking back at that time from his suite in the Vogue. "I didn't know what it was. I was ashamed of it, because it would be there even when things were good, and I would be saying to myself, 'Really, what have you got to complain about?' But for people who suffer from acute clinical depression, it is quite irrelevant what the circumstances of your life are."

Acute clinical depression. Hearing Leonard Cohen medicalizing his melancholia, the state so central to his work, so integral to the whole Cohen persona -- the tortured poet-saint, the dark prince of intellectual song -- was like hearing Martha Graham saying, "Oh, that was just Tourette's." Or Jack Nicholson explaining, "It was multiple-personality disorder all along." It's just so scientific, so 2001, and you don't want that from Cohen. You want to hear that it was ancient biliousness and opium. You don't want to think that "Chelsea Hotel #2" was the product of a serotonin deficiency, or an imbalance in dopamine. You want it to be the result of an encounter with Janis Joplin on an unmade bed, and her leaving in a limousine while he fell back into his suffering.

Still, being sweetly offered Godiva chocolates, you are happy that he seems better.

"You seem happy," I remark.

"For the first time in my life I am not depressed. I am happy."

"How did that happen?"

"It was a particularly pleasant surprise. The anguish just began to dissolve."

"Do you attribute this to your Zen practices? To life at Mount Baldy?"

"I just think my brain changed. I read somewhere that some of the brain cells associated with anxiety can die as you get older."

"So, it's chemistry, pure and simple?"

"I don't know, but gradually, within a small space of time, by imperceptible degrees, this depression lifted. It's been that way for two or three years now."

His meditation, his seclusion is still on my mind.

"Mr. Cohen?"

"Leonard."

"Leonard. What are you doing up there?"

"Knocking on wood."

On September 21, Leonard Cohen will turn sixty-seven. His advancing years have been the subject of a recent poem.

The old are kind

And the young are hot

Love may be blind

But desire is not

He doesn't look his age, but then again he does. Up close, he is a distinguished man of indeterminate years, his monk's shaved head grown into a thick salt-and-pepper Caesar cut. The lines bracketing his mouth, those which always looked a little like walrus tusks, are deeper, and they were always pretty deep. From the looks of the pretty woman in a red scoop-neck top in the bedroom of his suite, his female companions have not aged dramatically either. Then take a few steps back and Cohen's years surface. In the 1960s, one Winnipeg journalist wrote that Cohen had "the stoop of a crop picker," but now, more hunched, his belly more folded over, his wrists more limp, he has the posture of a man, as Cohen puts it, "reaching life's third act."

"Tennessee Williams had this famous quote: 'Life is a fairly well-written play except for the third act,'" says Cohen, flicking an ash off the table. "And I'm at the beginning of the third act. The end of the third act -- nobody has a handle on that one. But the beginning -- there is a certain relief for me here. It is palpable."

When Cohen was forty, his teacher Roshi, who is now ninety-four, looked at him and exclaimed, "Your generation? Finished!" It was a notion Cohen was happy to surrender to. "My generation was over. I thought, 'That was a load off.' You know, men in our culture mature very late, and there is every invitation to hold on to the notion of youth, to present yourself youthfully as long as you can."

Especially now, I suggest, with Viagra?

"Yes, maybe even later now, maybe later now." He laughs and offers me more coffee. "That boyish invitation can remain very strong. But still, when you reach your sixties, you do realize you are not totally in that particular game any longer. Then, you can start enjoying other mysterious social phenomena, like respect that is based exclusively on age. People are kind to you in a way they never were before. Policemen call you 'Sir.'"

Cohen may have his theory about his anxiety cells dying off, but the reality is that depression and anxiety -- especially in those who have known these things in younger years -- usually increase with age, owing to factors such as illness, the fear of death, and social isolation. Cohen may have believed himself too old for suicide in his late forties, but the rate of suicide among those in their "golden age" is increasing dramatically. Cohen, in this way, is once again going against the current.

"I think in the back of my mind, I always cherished some idea of an old man in a suit, smoking a cigarette, and delicately talking about his work to somebody," he whispers. "If you hang in there long enough, you begin to be surrounded by a certain gentleness, and also a certain invisibility. This invisibility is promising, because it will probably become deeper and deeper. And with invisibility -- and I am not talking about the opposite of celebrity, I mean something like 'The Shadow,' who can move from one room to another unobserved -- comes a beautiful calm."

Leonard Cohen believes that his new album carries with it a sense of "reconciliation" with himself. With his new-found peace of mind, he had reassessed his creative process, coming to the conclusion that his oeuvre was never simply the product of suffering. "I don't think my work has only come from that angle. Although that angle did allow for a lot." Over the last decade, Cohen wrote the lyrics for his new songs at Mount Baldy. "It's not a bad place to write," he says. "It's a very busy place, though. The monastic day is one governed by bells and clappers and showing up relentlessly at the various duties. There is a great deal of plumbing and carpentry and cooking to be done." Roshi suggested that Cohen write songs while in the meditation hall, a place where he spent six or seven hours a day.

All of Cohen's albums have been solo affairs, but the new one is more so. He has divested himself of collaborators to the point that he has only two: the singer Sharon Robinson, a fellow student of Roshi's and an old friend (Cohen is godfather to her son), and Leanne Ungar, who did much of the mixing. Gone are the big-name producers such as Phil Spector and the scores of studio musicians whose technical skill so outstripped Cohen's.

"The whole album reflects the relaxed condition under which it was made," says Cohen. Using a synthesizer and a computer loaded with music software, he composed many of the backing tracks himself, sending them to the hard drives of Robinson and Ungar for embellishments or modifications. These exchanges would continue until everyone was pleased. "It was a very leisurely process, and one amazing thing" -- Cohen's eyes are wide -- "is that the record really sounds like there is an orchestra behind me."

Not to my ears. But, at the risk of seeming unkind to my elders, it might sound like an orchestra to one of my grandparents. Some of the digital arrangements on Ten New Songs also made a friend of mine, a Cohen connoisseur, visibly distraught. They are not like ambient Pink Floyd synths, not like contemporary, crisp electronica synths, not even like the mellow, swooshy atmospherics of Cohen's last release, 1992's The Future. "It sounds like a guy in the subway with a keyboard who decided to burn a CD," said my friend.

Luckily for fans of Cohen, the lyrics are a delight. And his voice has a deeper confidence and is even more smoky thanks to his taking up tobacco again. (He had quit for a few years until a chain-smoking sage in Bombay had told him, "Not smoking? What's life for? Smoke!" "I bought a pack of cigarettes that day," says Cohen.) His thickened throat is set off by an almost startling simplicity in his lyrics. The words are plain. Undoubtedly, some will say they are lightweight, for this is not a style that carries with it the "Whoa! That's deep!" impressiveness of some of Cohen's most loved output. Yet, they convey an open-ended comfort and casual wisdom that feels fresh in Cohen's songwriting.

The ponies run, the girls are young,

The odds are there to beat.

You win a while, and then it's done,

Your little winning streak.

And summoned now to deal

With your invincible defeat,

You live your life as if it's real,

A thousand kisses deep.

Lately, there has been a revival of interest in Cohen's work. In Montreal, he visited the set of a large-scale feature-film adaptation of his 1963 novel The Favourite Game, being shot downtown. A new edition of the novel has recently been issued by his long-faithful publishers, McClelland & Stewart. "It has been doing enormously well," says Cohen's editor, Ellen Seligman, who is also awaiting the final manuscript of a collection of both new and old, unpublished poetry, tentatively titled The Book of Longing. "It just bears out my thinking that his writing will stand out for a new generation and for generations to come."

A well-oiled PR pitch for "mature" artists such as Cohen, is that they have begun "appealing to a younger audience." While this might be the case for Cohen's vintage musical output and for his writing, it is hard to imagine Ten New Songs piercing today's youth-centric, bubble-blowing popscape. It's just not that kind of material -- even for Montreal, where Cohen may be an icon, but the young Rufus Wainwright is the kids' tortured heartthrob songwriter du jour. The first single, "In My Secret Life," has had its video created by the hot director Floria Sigismondi, who has directed clips for, among others, Marilyn Manson. Still, Cohen concedes that it may not appeal to many outside his hard-core fan base -- now mainly the notoriously slow-buying, and lately, quite neglected, "adult contemporary" demographic. About this, he is pragmatic.

"Appealing to the young is a concern of record companies," says Cohen, lighting up another Vantage. "That is the buying market they see. Still, it seems to me like a great constituency that has money and interest and spare time is simply not being addressed by the commercial world. Eventually, I figure it will creep into the minds of some commercial entities that there are some people alive, not young, who still have interests. I have been hearing about connecting to the young for twenty or thirty years. At one point, you just say, 'Why?' The young people who are interested in my music always find their way to it."

The photographer, a cute little Québécois guy in pre-faded jeans and flip-flops, is shaking like a leaf and grinning from ear to ear. "Meester Cohen, it is such a great pleasure to meet you. It is an honour. I have waited all my life. . . ." The photographer's umbrellas and flashes are set up by the elevator on the mezzanine of the Vogue. Cohen is playing with a string of lapis-coloured beads in his right hand. "Take your time," he advises the young photographer. "We have time. It's so hard to work under pressure." Visibly more at ease, the photographer gives Cohen some directions: stand in front of the elevator doors, more to the left, more to the right. Ah! Perfect! Sooooper!

"You are a very happy photographer!" chuckles Cohen. "You are making me laugh!"

"You don't laugh often?" asks the picture-taker.

"Oh no, I do!" Cohen says.

Just as he leans on the elevator door for the shot, it opens. A squat, older woman in a red shell suit looks out, startled. The doors close. The doors open again. She wheels out her rolling suitcase, looking up in disbelief at the sight in black tailoring and the bright pocket square, holding the door open for her, like a knight for a princess. "Are you . . . are you Leonard Cohen? You look wonderful! I saw you perform twenty years ago in Toronto! Honey, look, it's Leonard Cohen!" The couple walks off. Cohen leans back on the door, grinning, and the photographer prepares the shot again. "Okay, Meester Cohen, are you comfortable?"

"Oh yes," he winks. "It's not a bad way to make a living. And anyway, I'm sure this will all work out very beautifully."

|